Aug. 29, 1985, Salmon NF (ID) Butte Fire IMT Aerial Ignition Firing Operation Entrapped 118 WFs & FFs, 73 Required Fire Shelters. Erratic Fire Weather. Pre-Purchasing Cases of Military Body Bags? P2

- Aug 6, 2025

- 48 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2025

Authors Fred J. Schoeffler, Jim Steele, and other contributing authors

Views expressed to "the public at large” and "of public concern"

DISCLAIMERS to follow: Please fully read the front page of the website (link below) before reading any of the posts. This includes that you must be at least 18 years of age or older to view this website and these posts.

This post is based on the author's professional judgement and opinions based on available evidences with no intention to defame individuals.

The authors and the blog are deny responsibility for misuse, reuse, recycled and cited and/or uncited copies of content within this blog by others. The content even though we are presenting it public, if being reused, must get written permission in doing so due to copyrighted material. Thank you.

Abbreviations used: Wildland Firefighters (WFs) - Firefighters (FFs).

All emphasis is added unless otherwise noted.

Link to the Part 1, Aug. 29, 1985, Salmon NF (ID) Butte Fire IMT Aerial Ignition Firing Operation Entrapped 118 WFs & FFs, 73 Required Fire Shelters. Erratic Fire Weather. Pre-Purchasing Cases of Military Body Bags?

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; For You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me.

Psalm 23:4 (NKJV)

Unlike the masses, intellectuals have a taste for rationality and interest in facts. Their critical habit of mind makes them resistant to the kind of propaganda that works so well on the majority.

Aldous Huxley

Figure 1. Payson HS Quinton (JQ) Butte Fire clearcut Snippet Source: JQ

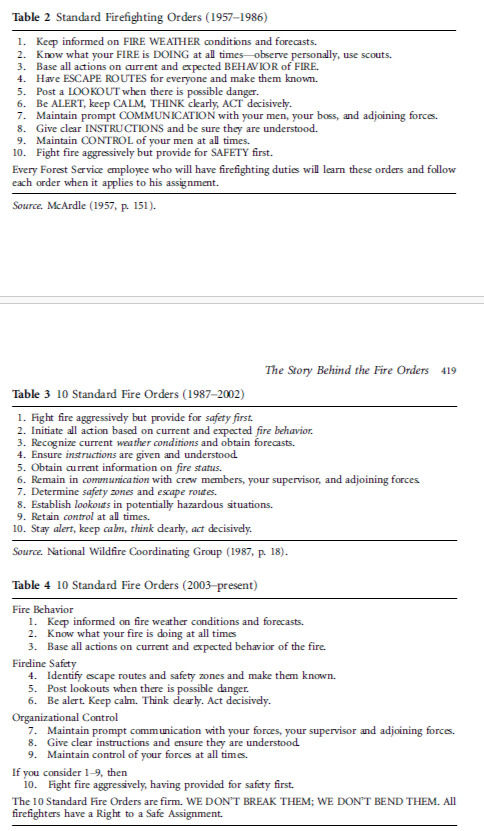

Figure 2. Fire Orders intents Snippets Source: Braunes, Fire Mgmt. Today

The Fire Orders should be used as originally intended. Not as a perfunctory list of items to be memorized by our firefighters.

Consider now several select historical Fire Order renditions from Dr. Jennifer Ziegler's "A Genealogy of Wildland Firefighter's 10 Standard Firefighting Orders" (2007) research papers and the 2012 YouTube History of the Fire Orders and WFSTAR: Fire Orders 2009 YouTube videos which are different videos with different titles and similar clips of Dr. Ziegler. This topic will be covered in more detail in Part 2 of this post. The Story Behind an Organizational List: A Genealogy of Wildland Firefighters’ 10 Standard Fire Orders in the publication: Communication Monographs. Vol. 74, No. 4, Dec. 2007, pp. 415- 442. This will be well worth your time to delve into because most of you reading this should and would find this research interesting and valuable as FFs, WFs, leaders, all of you interested in and engaged in wildland fire, and interested others seeking edification.

Figure 3. WFSTAR: Fire Orders 2018 Source: NWCG

Consider now Wisdom in the Lessons Learned Library: Work Ethics and Firefighter Identities in the Fire Orders. Eighth Intl. Wildland Fire Safety Summit, April 26-28, 2005, Missoula, MT. J. A. In: Butler, B.W., and Alexander, M.E. Eds. 2005. Eighth International Wildland Firefighter Safety Summit: Human Factors - 10 Years Later; April 26-28, 2005, Missoula, MT. The Intl. Assoc. of Wildland Fire, Hot Springs, SD. Jennifer A. Thackaberry, Ph.D. (Asst. Professor of Comm. at Purdue Univ.

Consider now Dr. Ziegler's (2007) Valparaiso Univ. research paper titled: The story behind an organizational list: A genealogy of wildland firefighters’ Ten Standard Fire Orders. Comm. Monographs, 74(4), 415-442.

"To invigorate research on the dialectic between lists and stories in communication, this study recommends adding context back to text by focusing on the enduring problems these forms are summoned to solve. A genealogy of one significant organizational list, wildland firefighters’ 10 Standard Fire Orders, shows how a list’s meaning resides less on its face and more in the discourses surrounding it, which can change over time. Vestiges of old meanings and unrelated cultural functions heaped upon a list can lead to conflicts, and can make the list difficult to scrap even when rendered obsolete for its intended purpose. Reconciling these layers of meanings and functions is thus not a technical problem but rather a rhetorical one. Implications for communication research are addressed.

Keywords: Organizational Communication; Dialectic of List and Story; Genealogy; Organizational Rhetoric; Wildland Firefighting

"This paper analyzes historic and contemporary documents about the Ten Standard Fire Orders in the Lessons Learned Center Library and elsewhere, to examine how justifications for these traditional safety rules have changed over time. Using ethical theory as a lens for analysis, the paper shows how the original Fire Orders attempted to codify an individual “virtue ethic” for firefighter safety, traditionally managed through narrative write-ups. However, their introduction simultaneously ushered in an individual “duty ethic” that would come to eclipse the virtue ethic over time. The findings from the South Canyon fire accident investigation reflect an organization at odds with whether it manages safety as a virtue or safety as a duty. The 2002 revision of the Fire Orders is said to be a return to basics. Whereas the early Fire Orders were intended to harness individual loyalty to the group as a way to repair defects in individual thinking, the analysis shows how the new Fire Orders are intended to function as a resource for individuals to repair defects in group reasoning. ... Therefore, while the new Fire Orders may indeed attempt to recover a virtue ethic, it is a distinctly organizational one. However, this is at odds with investigations that attribute accidents to violations, which [is] a view that is more compatible with an individual duty ethic." ... To study both text and context of a list, this article presents the genealogical method for studying a list, or an historic analysis of authorizing discourses that shows how a list has come to mean what it has for a particular community. The article also presents an actual genealogy of one significant organizational list, wildland firefighters’ 10 Standard Fire Orders, although the method could be applied to a variety of communication contexts. Most importantly, the analysis begins not with the list itself but with the enduring organizational problem to which a list, at one time, came to be viewed as a good solution: how to achieve control over people in a distributed context where they are working in a dangerous occupation that requires individual judgments in emergency situations in order to keep fires small and to keep crews safe from harm. The analysis shows how in organizational contexts, although a list may start out as an ostensibly good solution to enduring organizational problems, its very existence can give rise to new problems to address. One of those problems stems from the fact that a list can be authorized by a variety of different managerial ideologies over time, such that the very same list of items can come to mean vastly different things at different points in time. Furthermore, vestiges of old meanings can linger; thus, unearthing these old meanings can inform present day conflicts over the usefulness and appropriateness of a list. Moreover, a list can become imbued with many cultural functions unrelated to its original purpose that can make it difficult to modify or jettison even when the list is regarded as obsolete, and even when numerous other technical solutions have emerged to supplant it. In the case of the Fire Orders, after years of controversy and numerous proposed alternatives, it took the right narrative to help the community to change the list. Even then, the items on the list were only conservatively reordered. Ultimately, then, reconciling a list’s multiple meanings and cultural functions is a rhetorical problem, not a technical one. The article begins with a description of wildland firefighting and the role of the 10 Standard Fire Orders in that occupation. Then the organizational communication literature is reviewed as it relates to the problem of organizational control in distributed environments (particularly forestry), and to lists as organizational communication. Next, the genealogical method is introduced, and a genealogy of the Fire Orders is presented. At the conclusion of the article, the discussion addresses implications of the study not only for research on the dialectic of list and story in organizational contexts but also for understanding lists in/as communication more broadly.

Consider now Dr. Ziegler's research paper titled: The Story Behind an Organizational List: A Genealogy of Wildland Firefighters’ 10 Standard Fire Orders. Comm. Monographs. Vol. 74, No. 4, Dec. 2007, pp. 415-442.

Wildland Firefighting and the 10 Standard Fire Orders

"Fighting fires in national, state, and private forests is called wildland firefighting, as a way to distinguish it from structure firefighting in cities and towns, where different priorities, different tactics, and different equipment are used. Most forests have their own wildland fire crews, but when fires outgrow the capabilities of local resources, crews and equipment are dispatched from an interagency network that is centralized at the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) in Boise, Idaho. At the height of the summer fire season, up to 20,000 firefighters can be deployed on any given day (National Incident Information Center, 2006). Because firefighters may hail from different federal, state, and local agencies, the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) oversees standards for training and qualifications. As part of the basic firefighter training for initial ‘‘red card’’ certification, firefighters learn a list called the ‘‘10 Standard Fire Orders’’ (Fire Orders). In addition to completing workbook exercises and passing test questions on the Fire Orders, wildland firefighters are given stickers printed with the Fire Orders to paste into their helmets, as well as handbooks and pocket guides that contain the Fire Orders on the front or back covers. As will be shown below, there are 10 items on the list, but this is not the only reason that they are sometimes referred to as the ‘‘10 Commandments’’ of safe firefighting (Pyne, Andrews, & Laven, 1996). The original Standard Firefighting Orders, shown in Table 2, were introduced in 1957. Since then, the list has been revised exactly twice: In 1987 the items were reordered to spell ‘‘Fire Orders,’’ in order to aid better memorization, as evident in Table 3. Then, in 2003, the list was returned to roughly its original ordering in an attempt to get ‘‘back to basics,’’ as shown in Table 4. However, the seemingly stable surface of the Fire Orders as a list belies vast shifts in meaning and resulting controversies about the list that have taken place over its 50-year history.

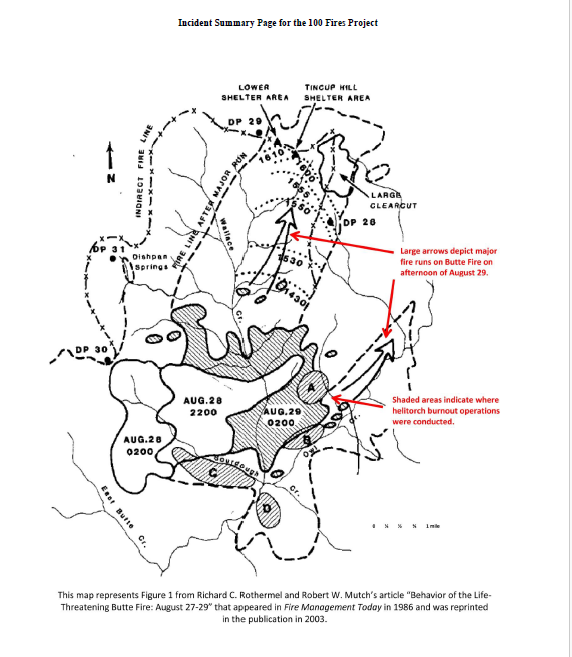

Figure 4. Standard FF Orders 1957-present [2007] Snippet Source: Ziegler

Leadership is taking someone to a place they normally wouldn’t go to by themselves. Joel A. Barker

Dr. Ziegler specifically mentions the 1985 Butte Fire. 1980s-1990s: Fire Orders as Duties After the mid-1950s, the average number of deaths by burnover went down from four per year to approximately one per year (NWCG 2004). "In celebrating the successful survival of 73 firefighters who had become entrapped on the Butte Fire in 1985, for example, Rothermel and Brown (2000) argued that ‘‘in part they owe their lives to the lessons from the Mann Gulch fire’’ (p. 9; see also Dombeck, 2000). Discussion of the Idaho Butte [F]ire is a good example of how this success rate is often attributed to the development of the Ten Standard Fire Orders (e.g., ). ... However, the Fire Orders that were in effect in the 1980s and 1990s were slightly different from those developed by the 1956 task force. They had been short[ened], reorganized to spell the mnemonic Fire Orders, making them easy to memorize and chant. Beyond these surface level changes, however, the work ethic that undergirded the Fire Orders had also shifted from a virtue ethic to a duty ethic, as evident in the direct commands (Fight, Initiate, Recognize, etc.). In other words, each emphasized direct actions to take (verbs) as opposed to virtues to embody (nouns)."

Ten Standard Fire Orders (ca. 1994)

1. Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.

2. Initiate all action based on current and expected fire behavior.

3. Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

4. Ensure that instructions are given and understood.

5. Obtain current information on fire status.

6. Remain in communication with crewmembers, your supervisor, and adjoining forces.

7. Determine safety zones and escape routes.

8. Establish lookouts in potentially hazardous situations.

9. Retain control at all times.

10. Stay alert, keep calm, think clearly, and act decisively."

Standard Firefighting Orders (1957-1986)

1. Keep informed on FIRE WEATHER conditions and forecasts.

2. Know what your FIRE is DOING at all times, observe personally, use scouts.

3. Base all actions on current and expected BEHAVIOR of FIRE.

4. Have ESCAPE ROUTES for everyone and make them known.

5. Post a LOOKOUT when there is possible danger.

6. Be ALERT, keep CALM, THINK clearly, ACT decisively.

7. Maintain prompt COMMUNICATION with your men, your boss, and adjoining forces.

8. Give clear INSTRUCTIONS and be sure they are understood.

9. Maintain CONTROL of your men at all times.

10. Fight fire aggressively but provide for SAFETY first.

Every Forest Service employee who will have firefighting duties will learn these orders and follow each order when it applies to his assignment.

Source. McArdle (1957, p. 151).

10 Standard Fire Orders (1987 -2002)

1. Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.

2. Initiate all action based on current and expected fire behavior.

3. Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

4. Ensure instructions are given and understood.

5. Obtain current information on fire status.

6. Remain in communication with crew members, your supervisor, and adjoining forces.

7. Determine safety zones and escape routes.

8. Establish lookouts in potentially hazardous situations.

9. Retain control at all times.

10. Stay alert, keep calm, think clearly, act decisively.

Source. National Wildfire Coordinating Group (1987, p. 18). Table 4 10 Standard Fire Orders (2003 present)

10 Standard Fire Orders (2003 present)

Fire Behavior

1. Keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts.

2. Know what your fire is doing at all times

3. Base all actions on current and expected behavior of the fire.

Fireline Safety

4. Identify escape routes and safety zones and make them known.

5. Post lookouts when there is possible danger.

6. Be alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively.

Organizational Control

7. Maintain prompt communication with your forces, your supervisor and adjoining forces.

8. Give clear instructions and ensure they are understood.

9. Maintain control of your forces at all times.

If you consider 1-9, then

10. Fight fire aggressively, having provided for safety first.

The 10 Standard Fire Orders are firm. WE DON’T BREAK THEM; WE DON’T BEND THEM.

All firefighters have a Right to a Safe Assignment

This nauseating 2018 sing-along Wildland Safety Training Annual Refresher (WFSTAR) YouTube video below, represented by the Figure 3b. Snippet may help explain why this is a real problem when they would stoop this low to utilize this cheesy method to encourage FFs and WFs to know and follow the Fire Orders.

Figure 3b. WFSTAR Fire Orders video Snippet Source: WFSTAR

It was all those gosh-darned troublesome Hot Shots (HS), Smokejumpers (SJ), and former HS and SJs individuals, and those that had achieved supervisor and managerial status that knew the true value of the original version that needed to be supported, that were the ones truly responsible for the return to sanity. Because they realized the value of the Fire Orders and the original intent and order as a progression of events that needed to be observed and heeded and put into place to fight fire safely, e.g. always first being the Fire Weather because it determines fire behavior, then seeing and scouting the fire personally and with scouts (where the word "scouts" was removed and never replaced), then identifying Escape Routes and Safety Zones, then communications, then control, and then - and only then - fight fire safely, etc.

4. Have ESCAPE ROUTES for everyone and make them known

Consider now Dr. Jennifer Ziegler's in-depth research paper titled: "How the '13 Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’ Became the '18 Watch Out Situations” Research Gate (2008) Jennifer A. Ziegler, Ph.D. Dept. of Comm. Valparaiso Univ. Valparaiso, IN 46383. Ziegler Author note. This analysis was compiled by examining articles and sidebars about the Watch Out Situations that appeared in Fire Management Notes according to the 2000 index (when it became Fire Management Today), along with other historic documents noted in the reference list. Ziegler document last updated: August 4, 2008.

Executive Summary

Although it is still a mystery about precisely when, where, or how the original 13 Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’ were developed, there is good reason to believe that they originated in the late 1960s, and most likely after 1967. Officially, there were 13 “Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’” in effect through the summer of 1987. Then, five items were added to the list when NWCG developed the “Standards for Survival” course later that year (1987). At that time, the name was also changed to 18 “Watch Out Situations,” and the sentence structure of each item was altered from the subjective “You are…” to a more objective description of each situation. 1987 was also the year the Fire Orders were reordered, and the Standards for Survival course and subsequent trend analyses of the Watch Out Situations emphasized how the two lists were supposed to work together. Although the Fire Orders were reordered in 2003, the list of Watch Out Situations has remained unchanged since 1987.

How the “13 Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’” Became the 18 Watch Out Situations

According to Braun, Gage, Booth, & Rowe (2001), the “13 Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’’(WOS) were originally created in the “mid to late 1960s” (p. 24); however, the actual list of WOS referenced in their article is dated “circa 1975” (p. 25) presumably because they were working from a document dated that year. According to a cumulative index created for Fire Management Notes (FMN) in 2000 (when the periodical changed to Fire Management Today), no articles or sidebars apparently mentioned the 13 Watch Out Situations during the 1960s and 1970s. However, in 1981 the Editor published “Thirteen Prescribed Fire Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’” that were sent in by John Maupin from Prineville, Oregon, which suggests that the suppression-related list of WOS was well known enough by then to imitate. And, in a study of wildfire accidents completed in 1979, the NWCG proposed collapsing the 13 WOS and the Ten Standard Fire Orders, into eight “Firefighting Commandments” that spelled the mnemonic “WATCH OUT” (NWCG, 1980, p. 3). (This proposal was apparently never approved.) Thus, although the original 13 WOS did not appear in FMN until 1985 (Editor, 1985), the fire community was conversant with them as far back as 1975. Late in 1987, another sidebar appeared in FMN that listed “Thirteen Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’” (Editor, 1987), which indicates that 13 was probably the official number through the summer of 1987. (Indeed, a comment by Morse [1988] about 140 entrapments having occurred during the 1987 fire season provides support for this assertion.) … From 13 to 18 … In late 1987, Morse and Monesmith (1987) published the article “Firefighter safety: A new national emphasis” in FMN, detailing a new “Standards for Survival” course and video that were being completed by “a small interagency working group” (p. 3) at the Boise Interagency Fire Center (now the National Interagency Fire Center). Quoting the Forest Service Director of Fire and Aviation at the time, the authors explained that the main purpose for the course was to teach “the proper recognition of the ‘Watch Out!’ situations followed by the initiation of the appropriate actions as defined in the Standard Fire Orders” (Morse & Monesmith, 1987, p. 3). … The authors also explained that five items had been added to the list of WOS for the course “to reflect critical hazardous conditions that are not readily recognized” (p. 3). The list of WOS had also been rearranged, according to the authors, “in the sequence in which the hazardous situations are most likely to occur” (Morse & Monesmith, 1987, p. 3). … When the 1987 sidebar is compared with Morse & Monesmith’s (1987) description of the Standards course, it becomes apparent that a few other changes were made to the WOS in 1987 in the development of the Standards for Survival course. First, the title of the list was changed from “Thirteen Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out’” to “Watch Out Situations” (Morse & Monesmith, 1987; cf. Editor, 1987). Second, each situation was reworded to reflect objective conditions rather than subjective ones. For example, “You feel like taking a little nap near the fire line” became “Taking a nap near the fireline” (Morse & Monesmith, 1987; cf. Editor, 1987). … (Note that Morse and Monesmith’s 1987 article was also the same article that announced the rearrangement of the Ten Standard Fire Orders to spell FIRE ORDERS. The changes made to the WOS in the development of the Standards for Survival course makes it reasonable to assume that the 1987 revision to the Fire Orders also occurred in the development of the Standards for Survival course.) … The availability of the Standards for Survival training course (NWCG, 1987) was announced in FMN in 1988 (Monesmith, 1988). In announcing the course, Monesmith (1988) listed the five items that had brought the number of WOS up to 18: “Fire not scouted and sized up (1), Safety zones and escape routes not identified (3), Uninformed on strategy and tactics (5), Constructing lines without a safe anchor (8), Attempting a frontal assault on the fire (10)” (p. 30).

The 18 Watch Out Situations

By 1989, the “18” WOS were well established, according to a sidebar that appeared in FMN (Editor, 1989). The following year, in 1990, Morse published a summary of a report called “Trend analysis of fireline ‘Watch Out Situations’ in seven fire-suppression fatality accidents,” where he also referred to the 18 WOS as “the NWCG Survival Checklist” (Morse, 1990, p. 10). … Consistent with the earlier rationale for the Standards for Survival course, Morse emphasized how the WOS were supposed to work along with the Fire Orders. He summarized the WOS that were most frequently overlooked on the seven incidents that were studied. He characterized these 5 as “blind spots” (he actually used the medical term scotoma [blind spot]) that were problematic because they prevented firefighters from taking the “dominant positive action,” – that is, obeying the relevant Fire Order – that could “counteract that negative situation” (p. 9). Based on the findings of the trend analysis, Morse concluded that “the relationship is clearly established between fireline fatalities and a lack of awareness or sensitivity to significant changes in fire behavior” (p. 11). … His article concluded with recommendations for local and national training. Through 2000 (the last year of the cumulative FMN index), the list of 18 WOS was repeated once again in a sidebar in 1992 (Editor, 1992). And, three other articles were published that referenced the WOS (e.g., Editor, 1995; Wilson, 1995; Valdez & Style, 1996). Although the Fire Orders were revised in 2003 (NWCG, 2003), the list of WOS has remained unchanged since 1987.

Limitations

It is important to note that this analysis only attempts to account for how the “18 Watch Out Situations” came about from the “13 Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out.’” As such, the analysis does not extend beyond 2000, having relied on the cumulative FMN index published that year. Furthermore, whereas Morse (1988) and Morse and Monesmith (1987) had

emphasized the “integrated” use of the WOS with the Fire Orders, this may not necessarily reflect the contemporary rationale behind their promotion and use (cf. Ziegler, 2007).

Future Research

What remains to be learned is when, how, and why the original 13 WOS were developed. Unfortunately, no background was provided in the TriData study (TriData, 1998), which otherwise referenced the WOS extensively. Based on research on the history of the Fire Orders (Ziegler, 2007), it is most likely that the original 13 WOS were developed after 1967. This is because there was no mention of the WOS in two key documents that grappled with a comprehensive approach to firefighter safety in the 1960s. First, a “Programmed Text” was developed by the Forest Service in 1965 as an instructional guide for firefighters to learn only the Fire Orders (Forest Service, 1965). Second, a 1967 Board of Review report for the 1966 Loop Fire investigation (Forest Service 1967), which simultaneously updated the original 1957 task force report that had led to the original development of the Fire Orders (USFS, 1957), focused only the Fire Orders. Like the Programmed Text, the Review Board report made no mention of any “Situations that Shout ‘Watch Out.’” For these reasons it seems reasonable to conclude that the WOS were developed after 1967, but before 1975 (Braun et al, 2001). … Based on a comment by Morse and Monesmith (1987), the original text of Carl Wilson’s study on “Some Common Denominators of Fire Behavior on Tragedy and Near-Miss Forest Fires” (e.g., Wilson, 1977) may hold some clues about the origin of the 13 WOS, particularly because that study covered the years 1926-1976. It is also possible that the original 13 WOS were developed informally and only integrated into policy after they were already in use, such as happened with LCES (Gleason, 1991; NWCG, 2006) and the Common Denominators of Fire Behavior on Tragedy Fires (NWCG, 2006; Wilson, 1977).

References

Braun, C., Gage, J., Booth, C., & Rowe, A. L. (2001). Creating and evaluating alternatives to the 10 Standard Fire Orders and 18 Watch-Out Situations. International Journal of Cognitive Ergonomics, 5(1), 23-35.

Editor. (1981). Thirteen prescribed fire situations that shout watch out! Fire Management Notes, 42(4): 10. (Contributed by John Maupin, Fire Staff Officer, Ochoco National Forest, Prineville, Oregon)

Editor. (1985). Thirteen Situations That Shout, “Watch Out!” Fire Management Notes, 46(3): 19. (Note: issue 3 not available on line)

Editor. (1987). Thirteen Situations that Shout “Watch Out!” Fire Management Notes, 48(3): 12.

Editor. (1989). “Watch Out!” Situations. Fire Management Notes, 50(4): 29.

Editor. (1992-1993). “Watch Out” Situations. Fire Management Notes, 53–54(1): 31.

Editor. (1995). A checklist from an incident management team’s safety officer. Fire Management Notes, 55(4): 19. (Note: Contributed by Tony Dietz, then a member of a Great Basin interagency incident management team)

Gleason, P. (1991). LCES—A Key to Safety in the Wildland Fire Environment. Fire Management Notes, 52(4), 9.

Monesmith, J. (1988). Standards for survival. Fire Management Notes, 49(3): 30–31.

Morse, G. A. (1990). A trend analysis of fireline “Watch Out” Situations in seven fire suppression fatality accidents. Fire Management Notes, 51(2): 8-12.

Morse, G. A., & Monesmith, J. R. (1987). Firefighter safety: A new national emphasis. Fire Management Notes, 48(4): 3–5.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group. (1980). Preliminary report of task force on study of fatal /near-fatal wildland fire accidents. Boise, ID: Author.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group. (1987). Standards for Survival: Student workbook (PMS 416-2). Boise, ID: Author.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group. (2003, Feb 25). Revision of the Ten Standard Firefighting Orders (Transmittal Memo). Boise ID: National Interagency Fire Center.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group Incident Operations Standards Working Team. (2006, Jan). Incident Response Pocket Guide (PMS #461/NFES #1077). Boise, ID: Author.

Tri-Data Corporation. (1998). Wildland firefighter safety awareness study: Phase III - Key findings for changing the wildland firefighting culture. Arlington, VA: Author.

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Division of Fire Control. (1957). Report of task force to recommend action to reduce the chances of men being killed by burning while fight[ing] fire. Washington DC: Author.

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Division of Fire Control. (1965). 10 Standard Fire Fighting Orders: A programmed text for training fire fighters to know and apply the Ten Standard Orders to fire situations (TT-8-5100). Washington, DC: Author.

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. (1967). Report of the fire safety

review team: A plan to further reduce the chances of men being burned while fighting fires. Washington DC: United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Division of Fire Control.

Valdez, M., & Style, J. R. (1996). Shout, “Watch out—Snag!” Fire Management Notes, 56(3): 26–27. (Note: entire volume unavailable online)

Wilson, C. C. (1977) Fatal and near-fatal forest fires: the common denominators. The International Fire Chief 43(9).

Wilson, N. L. (1995). Safety first: Brain vs. brawn. Fire Management Notes, 55(4): 31-32.

Ziegler, J. A. (2007). The story behind an organizational list: A genealogy of wildland

firefighter's Ten Standard Firefighting Orders. Communication Monographs, 74(4), 415 - 442.

Investigators Jukala and Putnam encourage utilizing caution when following and heeding the established tried-and-trued Rules of Engagement (RoE) e.g. Fire Orders and Watch Out Situations here: "Although entrapments can't always be avoided, you can make it unlikely by following the Ten Standard Fire Orders ... Knowing the fire situations that shout 'Watch Out' ... knowing the major fire behavior common denominators that lead to tragedies or near miss fires. ... Use the fire shelter as a last resort. Follow proven escape principles first." (USFS - Fire Management Notes, 1988, 47, 2) Dr. Putnam was the Lead Investigator who refused to sign off on the 1994 South Canyon Fire because of the many lies and inaccuracies. (WLF LLC, 1994-1995); 20 Years After the South Canyon Fire - Never Again, Billie Stanton, Magic Valley News, Parts 1-4 (2004). This source is excellent and worthy of further review.

Consider another of Dr. Putnam's worthy research papers. Fire Safety. Up in Smoke? Dr. Ted Putnam. Everyone Goes Home (2015)

"Lack of fire management support for human factors, Why safety is not No. 1, No one can follow the 10 standard fire orders, Most wildland fire entrapment investigations involve covering up evidence, Active concern for safety is punished, We are a long way from becoming a learning organization, Summary - Currently the fire organization is not very proactive in making safety a major influence in strategies and tactics. Getting the job done, money and image concerns push firefighters into taking excessive risk. What is needed organizationally is truthful fire "investigations, an honest reporting system that tracks physical, mental, cultural and social aspects of firefighting and a willingness to become a learning organization. If safety is ever to become No. 1 in the fire community then the fire community must be willing to spend more time, money and effort to make it No. 1. The fire community must get beyond its superficial practices like saying over and over again that safety is No. 1 without any true, longer-term, institutionalized commitment. Part of this commitment should involve adopting CRM throughout the organization, following-up on the Tri-Data contract recommendations and promoting clearer thinking through the practice of mindfulness."

"Lack of fire management support for human factors, Why safety is not No. 1, No one can follow the 10 standard fire orders, Most wildland fire entrapment investigations involve covering up evidence, Active concern for safety is punished, We are a long way from becoming a learning organization, Summary - Currently the fire organization is not very proactive in making safety a major influence in strategies and tactics. Getting the job done, money and image concerns push firefighters into taking excessive risk. What is needed organizationally is truthful fire "investigations, an honest reporting system that tracks physical, mental, cultural and social aspects of firefighting and a willingness to become a learning organization. If safety is ever to become No. 1 in the fire community then the fire community must be willing to spend more time, money and effort to make it No. 1. The fire community must get beyond its superficial practices like saying over and over again that safety is No. 1 without any true, longer-term, institutionalized commitment. Part of this commitment should involve adopting CRM [Crew Resource Management] throughout the organization, following-up on the Tri-Data contract recommendations and promoting clearer thinking through the practice of mindfulness."

Figure 4. History of the Standard Fire Orders Source: WLF LLC

Based on the fact that many of us there on Aug. 29, 1985, explicitly and/or implicitly refused to give the order to deploy fire shelters, reflect on this "official" instructive lesson. The Art of Refusing Risk & Respecting Extreme Fire Behavior Wildland Fire Leadership (WFL, 2015)

"There is an art to risk assessment. What may seem impossible to one person may seem achievable by another. Effective fire leaders develop the art through experience as students of fire and leadership. We know from our history that human factors are critical to our success or failure. Good fire leaders employ numerous methods, continually develop situation awareness, and develop their people to provide the critical feedback to keep everyone safe."

Wildland Fire Leadership Challenge - Digging a Little Deeper

Charlie Caldwell, former Redding Hotshot Supt, refusing assignments.

How to Properly Refuse Risk - IRPG

"Every individual has the right and obligation to report safety problems and contribute ideas regarding their safety. Supervisors are expected to give these concerns and ideas serious consideration. When an individual feels an assignment is unsafe they also have the obligation to identify, to the degree possible, safe alternatives for completing that assignment. Turning down an assignment is one possible outcome of managing risk.

A “turn down” is a situation where an individual has determined they cannot undertake an assignment as given, and they are unable to negotiate an alternative solution. The turn down of an assignment must be based on an assessment of risks and the ability of the individual or organization to control those risks. Individuals may turn down an assignment as unsafe when (1) There is a violation of safe work practices (2) Environmental conditions make the work unsafe (3) They lack the necessary qualifications or experience (4) Defective equipment is being used.

The individual directly informs their Supervisor they are turning down the assignment as given. Use the criteria outline in the Risk Management Process (Firefighting Orders, Watch Out Situations, etc.) to document the turn down.

The supervisor notifies the Safety Officer immediately upon being informed of the turn down. If there is no Safety Officer, the appropriate Section Chief or the Incident Commander should be notified. This provides accountability for decisions and initiates communication of safety concerns within the incident organization.

If the supervisor asks another resource to perform the assignment, they are responsible to inform the new resource that the assignment was turned down and the reasons why it was turned down.

If an unresolved safety hazard exists or an unsafe act was committed, the individual should also document the turn down by submitting a SAFENET (ground hazard) or SAFECOM (aviation hazard) form in a timely manner. These actions do not stop an operation from being carried out. This protocol is integral to the effective management of risk as it provides timely identification of hazards to the chain of command, raises risk awareness for both leaders and subordinates, and promotes accountability.

[Incident Response Pocket Guide, pp.19-20]

Jennifer Ziegler

"To invigorate research on the dialectic between lists and stories in communication, this study recommends adding context back to text by focusing on the enduring problems these forms are summoned to solve. A genealogy of one significant organizational list, wildland firefighters’ 10 Standard Fire Orders, shows how a list’s meaning resides less on its face and more in the discourses surrounding it, which can change over time. Vestiges of old meanings and unrelated cultural functions heaped upon a list can lead to conflicts, and can make the list difficult to scrap even when rendered obsolete for its intended purpose. Reconciling these layers of meanings and functions is thus not a technical problem but rather a rhetorical one. Implications for communication research are addressed. ... Although this study is not focused on identification per se, the story behind the Fire Orders can nevertheless inform historic shifts in managerial ideologies regarding the presumed relationship among individuals, groups, and organizations, including the possibility of achieving control in distributed work contexts. ... The Story Behind the Fire Orders - After a disastrous fire called the Big Blowup of 1910, the fledgling Forest Service essentially received a ‘‘blank check’’to address wildland fire on public lands (Pyne, 1997). Since the inception of this ‘‘industry,’’wildland firefighting organizations have faced an enduring problem which still exists today: how to keep fires small while simultaneously keeping everyone safe, but in a distributed and dangerous work context that relies on individual judgments made under emergency conditions. ... Originally, this problem was managed through write-ups that appeared in Forest Service periodicals such as Fire Control Notes, where stories of successes and failures were shared. Success stories praised heroes like Ranger Urban Post, who had exhibited on the 1937 Blackwater Fire a seemingly ‘‘unconscious’’ability to simultaneously control a fire while ‘‘providing a running accompaniment of a plan for the safety of the crew,’’ thus limiting the fatalities in that tragic fire to only 11 (Division of Fire Control, 1937, p. 305). ... Conversely, write-ups about failures shamed Rangers and others who either failed to control a fire or failed to keep a crew safe. One Ranger from Ocala, Florida, for example, pinned the blame for the growth of the 1938 Pleasant Flat Fire upon a fellow Ranger who he felt had been unable to ‘‘make efficient use of the manpower and equipment’’ available to him at the time (Headley, 1939/2003a, p. 21). However, the editor added sympathetically that the wayward Ranger should know that even the ‘‘big shots in fire control suffered from the same inability,’’ but that this ‘‘should not deter him from seeking to be mentally prepared’’ for the next fire (p. 21). ... In these early years (approximately 19373 (sic) 1956), the mode of control was substantive: If fire control and crew safety were achieved, then a Ranger would be singled out as a hero; if not, then he would be potentially ridiculed. Nevertheless, he would be offered the opportunity to become a hero next time. This was consistent with the ‘‘welfare capitalism’’ managerial ideologies prevalent in the era before 1955 (Barley & Kunda, 1992), which embraced the cultivation of personal growth on the job. ... Unfortunately, relying on control through narratives meant relying on a relatively slow process of trial and error to facilitate crew leader judgments. Even though, like NASA’s ‘‘Monday Notes’’ (Tompkins, 2005), the periodical was intended as a way for Rangers to share updates about fire suppression across the nation, Fire Control Notes was only published once a month. This was too slow for firefighters who faced intense and potentially deadly fires in the short span of a summer. Firefighters also started to express concerns that this mode of evaluation seemed at times to be capricious. As the Forest Service modernized into a national fire program in the 1930s and 1940s, particularly with the influx of workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps (Pyne, 1997), the agency began to bureaucratize. As a result, there came increasing calls for more ‘‘objective’’ standards for evaluation in fire operations. ... For example, in one write-up, a Ranger from Mississippi complained that the same action that ‘‘merits commendation in hundreds of cases’’ could at other times be criticized as ‘‘poor judgment’’ based solely on the outcome of the fire (Headley, 1940/2003b, p. 24). In that case, the Ranger proposed, it would be better to adopt a rule for everyone to follow in every case, and one that erred on the side of caution (p. 24). In short, a need was emerging for a tool that could help firefighters to develop good judgments in the field more quickly, and one that could apply ‘‘objectively’’ to most, if not all, situations. ... 10 Standard Firefighting Orders, 1957-1986 - In 1957, Chief R. E. McArdle introduced the 10 Standard Firefighting Orders (Firefighting Orders), to be memorized and followed by all Forest Service employees who were assigned to fire duties (McArdle, 1957). This section explains how the original Firefighting Orders were developed, and how they came to be perceived as a good solution, not only to the original problem of control in the distributed and dangerous working environment, but also to new problems introduced by the narrative approach as discussed above. ... ‘‘Coolheads’’ and ‘‘sinners.’’ In 1956, the Inaja Fire killed 11 inmate crew firefighters in California. Yielding to public pressure, in 1957, Chief McArdle convened a task force to investigate ways to ‘‘reduce the chances of men being killed by burning while fighting fire’’ (US Department of Agriculture Forest Service [Forest Service], 1957). The task force conducted a trend analysis of fatal fires from the previous 20 years, paying particular attention to five fires where 10 or more firefighters had been killed at once. They identified 11 items that the worst fires had had in common, and referred to these as ‘‘sins of omission’’ by ‘‘men who know better’’ but who ‘‘just did not pay adequate attention’’ to small details when it mattered most (p. 8). ... While their trend analysis could identify what the ‘‘sinners’’ did wrong on tragic fires, it could not really explain what the ‘‘heroes’’ had been doing right on the successful ones. All the task force knew was that they had identified 11 levers that potentially led to catastrophe. They did acknowledge that lives saved in near-miss fires could be attributed to ‘‘some coolhead [who] sized up a local change in fire behavior and figured out what would happen in time to get the men to safety’’ (Forest Service, 1957, p. 4). Thus, they imputed, some fires were successful because ‘‘someone did not fail in one of these critical categories’’ (p. 4). Therefore, the search was on for a good solution that might help firefighters to not forget things that they already knew in the midst of an emergency. ... Because the analysis was being conducted after the Second World War, the Forest Service borrowed the military approach to controlling the individual by harnessing loyalty to the group; namely, to cause a soldier to fear letting down the men in his unit more than he feared the enemy. This approach would have been familiar to veterans who had joined the wildland fire service after returning from the Second World War (Pyne, 1997). Thus, the Standard Firefighting Orders were modeled after military ‘‘General Orders.’’ The rationale was that using the Firefighting Orders to harness individual loyalty to the group would help to stem defects in individual remembering until such time as a firefighter’s reasoning process was as ‘‘automatic’’ as the coolheads’ judgments seemed to be. This was the same approach to judgment formation as the prior stories of praise and blame; however, now the list of Standard Firefighting Orders offered an instrument, or an explicit reminder list to support the firefighter until the principles were internalized and applied seemingly automatically (cf. Kaufman, 1960/1967). ... A list of virtues. Now that the context for the development of the original Standard Firefighting Orders has been explained, ... Originally, the task force had planned to release a mnemonic list that spelled out the warning ‘‘Fire Scalds.’’ However, before it was issued, the Chief deleted one item, revised another, and added an additional order: ‘‘Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first’’ (McArdle, 1957). In light of the discussion above, this particular Firefighting Order can be understood as capturing the simultaneous virtues of the coolheads: keeping the fire small (i.e., ‘‘fight fire aggressively’’) while keeping everyone safe (i.e., ‘‘fight fire aggressively’’). ... Although it was borne of the impetus of standardization, the original list was not entirely bureaucratic as Edwards (1979/1994) might define it, because there were no one-for-one consequences for failing to follow the Firefighting Orders. ... the list represented something more like a codification of firefighter virtues, or a list of qualities that a good firefighter would come to embody in learning how to keep the fire small while also keeping the crew safe. Various experiences would presumably give the firefighter the chance to work through all nine items. Once he mastered them, the firefighter could literally become the 10th, or one of the praiseworthy ‘‘coolheads’’ who could realize the simultaneous goals of keeping the fire small and the crew safe. ... 10 Standard Fire Orders, 1987 2002 - In 1987, the list was revised for the first time in 30 years. This section explains why the Firefighting Orders were revised and how that revision was perceived as a good solution not only to the original problem of control, but also to new problems that had cropped up as a result of the adoption of the original list. ... Violators and adherents. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the 10 Standard Firefighting Orders were included in basic training for all Forest Service firefighters. Moore (1959) directed instructors to emphasize number 10 in particular: ‘‘Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.’’ In a statement reflecting the paramilitary era in which it was written (Pyne, 1997), Moore claimed that training was not complete ‘‘until the trainee is convinced that the safest, most effective way to fight forest fires is to understand the enemy and to attack it aggressively, applying sound suppression tactics until it is beaten’’ (p. 60). Similarly, a firefighting textbook from 1965 emphasizes ‘‘fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first’’ as the ‘‘overall Fire Order to which the other nine are directed’’ (Forest Service, 1965, p. 54). ... Sometime in the 1960s, however, the Fire Orders began to shift from an individual list to an organizational one. The Firefighting Orders had clearly taken on symbolic significance when in 1967, the Washington Office of the Forest Service overrode the recommendation of a review panel who had recommended adding two more items to the list, one of which was building fires downhill. Instead, they created a separate ‘‘Downhill Fireline Construction Checklist.’’ Additionally, reflecting the rise of systems rationalism of the time (Barley & Kunda, 1992), the Firefighting Orders began to be used as a checklist to evaluate individual fires. The write-up of the heroic Cherokee Incident near miss appears to be the first use of the list as such a litmus test. After a summary of the list of factors that Nix (1960) believed had led to ‘‘control of the fire without injury or worse,’’ the editor inserted the comment, ‘‘in other words, knowledge and application of the 10 Standard Firefighting Orders’’ (p. 9).

Later the list of Firefighting Orders began to be used to analyze fatality fires. In 1967 the investigation of the Sundance Fire noted faulty ‘‘adherence’’to the Firefighting Orders. Then in 1977, the investigation into the Cart Creek Fire cited a lack of ‘‘compliance’’with the Firefighting Orders and ‘‘violation’’ of numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10. In 1979, the investigation into the Ship Island Fire recommended that trainers place strong emphasis on the message that ‘‘the 10 Standard Firefighting Orders are not to be deviated or broken’’ (Forest Service, 1979, p. 7). The investigators added, (p. 7). ... In 1990 the investigation report of the Dude Fire, which killed six firefighters in Arizona, included ‘‘violations of the Fire Orders’’ on a list of causal factors for that tragedy. This solidified the use of the Fire Orders as a checklist for accident investigations for at least the next decade. The shift of the Fire Orders from an individual list of virtues to an organizational list of duties is most evident when comparing what investigation teams complained about in 1957 as compared to what they complained about in 1994: Whereas in 1957 the task force complained that the ‘‘sins of omission’’ that they had identified were appearing ‘‘time and time again’’ before boards of review, by 1994, the South Canyon report complained that ‘‘time and time again’’ fatal accidents were being traced to ‘‘violations of’’ one or more of the Fire Orders (US Department of Interior Bureau of Land Management [BLM], & Forest Service, 1994, p. 34). ... Aside from reflecting the emergence of systems rationalism in the 1970s and 1980s (Barley & Kunda, 1992), the increasing bureaucratic use of the Standard Firefighting Orders can be traced to a shift in legitimacy for the Forest Service as identified by Bullis and Tompkins (1989): ‘‘[E]xpert management (based on values) gave way to management based on (political) public will’’ (p. 291). Bullis (1993) also observed increasing cultural fragmentation along occupational lines (see also DiSanza & Bullis, 1999). Indeed, Pyne (1997) identified the 1970s and 1980s as the era when the Forest Service began to harness ‘‘information’’ to control fires, including by expanding research about weather, prescription fires, equipment, and safety measures. As these items were processed into inputs and outputs, so were the Firefighting Orders. ... Wildland firefighting was also expanding beyond the purview of the Forest Service during that time. After a disastrous fire season in California in the early 1970s, a task force nicknamed FIRESCOPE developed the Incident Command System (ICS) as the basic structure that federal, state, and local firefighters still in use today to unify command and to coordinate resources on all large wildland fires (Monesmith, 1983). In 1976, the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) was created to develop and maintain additional interagency standards (Wilson, 1978). In the mid-1970s, the NWCG adopted the Fire Orders4 as ‘‘standards for survival’’ for all interagency wildland firefighters, not just Forest Service employees (Monesmith, 1988). ... However, in the mid-1980s, Morse and Monesmith (1987) noted that firefighters were no longer memorizing the Standard Firefighting Orders. They complained that the list was like the 10 Commandments: ‘‘Individuals readily admit that they believe in their worth but they have some problems when asked specifically to identify and follow them’’ (p. 3). This is not to say that firefighters were necessarily fighting fires badly, but rather that they now tended only to pay attention to rules that actually had consequences for breaking them. This reflects the same decline in identification and move toward bureaucratization that was identified by Bullis and Tompkins (1989). As a result, the 10 Standard Firefighting Orders were reorganized in 1987 to make them easier to memorize and follow. ... A list of duties. Now that the context for the 1987 revision has been explained, the characteristics of this second iteration of the Fire Orders can be analyzed. As shown in Table 3, the 1987 list, now called Fire Orders, was rearranged into a deliberate mnemonic (F-I-R-E O-R-D-E-R-S) that was meant to be memorized. Besides the rewording and reordering of the individual items, the intended use of the list had also changed. Now the emphasis was on discrete items that were all to be followed at once. Also, the 10th Fire Order, ‘‘fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first’’ had been placed at the top of the list, and was being promoted as the ‘‘overall safety rule’’ that applied to all work contexts (such as driving) and not just to firefighting (Morse & Monesmith, 1987, p. 4). Thus, the meaning of this primary Fire Order was no longer strictly literal but also metaphoric: A firefighter should always be aggressive in his or her duties, but only after providing for safety. ..."

The Standard Firefighting Orders (1957-1986)

1. Keep informed on FIRE WEATHER conditions and forecasts.

2. Know what your FIRE is DOING at all times* observe personally, use scouts.

3. Base all actions on current and expected BEHAVIOR of FIRE.

4. Have ESCAPE ROUTES for everyone and make them known.

5. Post a LOOKOUT when there is possible danger.

6. Be ALERT, keep CALM, THINK clearly, ACT decisively.

7. Maintain prompt COMMUNICATION with your men, your boss, and adjoining forces.

8. Give clear INSTRUCTIONS and be sure they are understood.

9. Maintain CONTROL of your men at all times.

10. Fight fire aggressively but provide for SAFETY first.

Every Forest Service employee who will have firefighting duties will learn these orders and follow each order when it applies to his assignment.

Source. McArdle (1957, p. 151).

10 Standard Fire Orders (1987-2002)

1. Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.

2. Initiate all action based on current and expected fire behavior.

3. Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

4. Ensure instructions are given and understood.

5. Obtain current information on fire status.

6. Remain in communication with crew members, your supervisor, and adjoining forces.

7. Determine safety zones and escape routes.

8. Establish lookouts in potentially hazardous situations.

9. Retain control at all times.

10. Stay alert, keep calm, think clearly, act decisively.

Source. National Wildfire Coordinating Group (1987, p. 18). Table 4

The following portion is from the relevant NWCG website accessed May 2025 regarding the modern, most current 10 Standard Firefighting Orders due to difficulty accessing Dr. Ziegler's "A Genealogy of Wildland Firefighters' 10 Standard Fire Orders" research paper. "The NWCG Parent Group just approved the revision of the Ten Standard Fire Orders per their original arrangement. The original arrangement of the Orders is logically organized to be implemented systematically and applied to all fire situations." Ziegler's maiden name is Thackaberry, and is listed in the sources and research papers below.

Fire Behavior

1. Keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts.

2. Know what your fire is doing at all times.

3. Base all actions on current and expected behavior of the fire.

Fireline Safety

4. Identify escape routes and safety zones and make them known.

5. Post lookouts when there is possible danger.

6. Be alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively.

Organizational Control

7. Maintain prompt communications with your forces, your supervisor and adjoining forces.

8. Give clear instructions and insure they are understood.

9. Maintain control of your forces at all times.

If 1‐9 are considered, then...

10. Fight fire aggressively, having provided for safety first.

The 10 Standard Fire Orders are firm. We don’t break them; we don’t bend them. All firefighters have the right to a safe assignment.

This author notes that the Fire Orders "rearranged into a deliberate mnemonic (F-I-R-E O-R-D-E-R-S)" statement must be addressed at this juncture for historical clarification and edification. The Fire Orders were initially arranged in a progressively meaningful manner. Fire Behavior, Organizational Control, Fireline Safety, then and only then, Fight Fire!

Please take the time to carefully evaluate the following 1987-2002 Fire Orders rearrangement, alleged "Good Idea" to move Fire Order No. 10 to No. 1 - "Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first." Without initially knowing the fire weather, which determines the fire behavior. manner and order below that the NWCG allowed these life-saving Fire Orders to dangerously and intentionally become"official." Clearly, this should be obvious; if one were to literally follow these in the order they are listed below, they would more than likely be burned over, entrapped, or dead rapidly! Those of us who realized this intentionality and wisely and with purpose chose to stay-the-course with the common-sense manner of fighting fire and continued to push back hard, persistently, professionally, and tactfully for years to get this changed.

10 Standard Fire Orders (1987-2002)

1. Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.

2. Initiate all action based on current and expected fire behavior.

3. Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

4. Ensure instructions are given and understood.

5. Obtain current information on fire status.

6. Remain in communication with crew members, your supervisor, and adjoining forces.

7. Determine safety zones and escape routes.

8. Establish lookouts in potentially hazardous situations.

9. Retain control at all times.

10. Stay alert, keep calm, think clearly, act decisively.

This deliberate mnemonic change was clearly an outright "Attack of the Good Idea People" because they claimed that there were many who claimed they had a difficult time memorizing the most important 43-life-saving words in the wildland fire world. And yet, they made it through High School and College memorizing 43 things. And those ardent Sports Aficionados, Buffs, Enthusiasts, etc. were able to memorize hundreds of their favorite Players' and Teams' statistics with no problems. So then, how are those going to save FF and WF lives? Indeed, it was the Hot Shots (HS), Smokejumpers (SJ), former HS and SJs, and others who had achieved supervisor and managerial status who knew the common-sense safety value of the original version that needed to be supported. We were the ones responsible for the return to sanity because we realized the value of the Fire Orders and the original intent and order as a progression of events that needed to be observed and heeded, and put into place to safely fight fire. First off, you must know the Fire Weather, then see and scout the fire personally and use scouts (when the "scouts" portion was removed and never replaced), then identifying Escape Routes and Safety Zones, then Communications, and Control, and then -and only then - Fight fire safely, etc. Please consider and adopt the Fire Orders 101 this author designed below for those of you who have never learned them by heart.

Fire Orders 101

1. Weather

2. Observe

3. Actions

4. ERs & SZs

5. Lookouts

6. Reevaluate

7. Communicate

8. Instructions

9. Control

10. Fight Fire

The "rearranged into a deliberate mnemonic (F-I-R-E O-R-D-E-R-S)" statement must be addressed at this juncture for historical clarification and edification. This deliberate mnemonic change was clearly an Attack of the Good Idea People because they claimed that they had a difficult time memorizing the most important 43-life-saving words in the wildland fire world. Yet they made it through High School and College and the Sports Aficionados could memorize hundreds of sports individual and teams statistics. So how was that going to save lives? It was the Hot Shots (HS), Smokejumpers (SJ), and former HS and SJs that had achieved supervisor and managerial status that knew the value of the original version that need to be supported that were the ones responsible for the return to sanity because they realized the value of the Fire Orders and the original intent and order as a progression of events that needed to be observed and heeded and put into place to safely fight fire, e.g. Fire Weather, see and scouting the fire personally and with scouts (which was removed and never replaced), then identifying Escape Routes and Safety Zones, then communications, and control, and then -and only then - fight fire safely, etc. ...

(Hearit, 1995) in a time of crisis. ... As with most discursive transitions, however, the migration of the Fire Orders from a list of virtues to embody, to a list of duties to be followed, was not a clean break. In 1994, as in 1990, the duty frame was invoked in the explanation for the 14 deaths on the South Canyon Fire in Colorado: The report found that firefighters had violated 8 out of the 10 Fire Orders (BLM & Forest Service, 1994). Nevertheless, vestiges of the Fire Orders as personal virtues were evident in the accompanying determination that it was the supervisors’ and firefighters’ ‘‘can-do attitude’’ that had caused them to violate the Fire Orders (Thackaberry, 2006; see also Larson, 2003; Maclean, 1999). It is unclear which caused the wildland fire community more pain: the recounting of the organizational infractions, or the public shaming of the firefighters. A parent of one fallen firefighter bemoaned that it was as if the investigators had said that ‘‘my child wasn’t intelligent enough to save his own life’’ (in Wolfinger & Bacon, 2002). ... A public struggle. Resistance soon surfaced that revealed how some firefighters had been regarding the authority of the Fire Orders, and how they had actually been using them on the ground. For example, law student and seasonal firefighter Quentin Rhoades (1994) wrote an op-ed piece for his local newspaper where he argued that safe firefighting required firefighters to ‘‘bend’’ the rules on a fairly regular basis. Not long after, Reason (1997) presented a similar claim in Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Once rules become procedures, he argued, an employee’s space of action is constricted, yet the operating environment has not changed. Thus, the true skill becomes knowing which rules to violate, and when (Reason, 1997, p. These kinds of sentiments received a swift official response in 1995 from the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior, who issued a memo admonishing th Fire Orders are firm; we don’t bend them we don’t break them" them(Glickman & Babbitt, 1995). They also threatened a ‘‘zero tolerance policy’’ for infractions. When a similar dispute arose after the investigation into the Thirtymile Fire in 2001, where firefighters were found to have broken all 10 items on the list, the Fire Orders were now clarified as ‘‘rules of engagement’’ (Williams, 2002; see Thackaberry, 2004, for further discussion). ... Thus, an explicit and very public tug of war was now under way over the precise authority of the Fire Orders. The next section shows how although numerous solutions were proposed, the parties were deadlocked until the right narrative came along to help the wildland fire community to revise the list and to move forward. ... 10 Standard Fire Orders, 2003 Present ... The Fire Orders were revised again in 2003 in an attempt to get ‘‘back to basics’’; that is, to try to recapture what was understood to be the spirit of the original 1957 Fire Orders. This section explains why the Fire Orders were revised back to something close to their original ordering in 2003, and how that revision was perceived at the time to be a good solution, not only to the enduring problem of control in the distributed and dangerous work environment, but also to new problems that had emerged as a result of the 1987 revision, including how they were being invoked in accident investigations. ... The Problem of the List - The struggle over the precise authority of the Fire Orders described above continued into the late 1990s and early 2000s. One outspoken smokejumper who had become an equipment specialist argued that if the Fire Orders were consistently being found to have been violated, then perhaps they might be impossible to follow in the first place (Putnam, 2001b; see also Braun, Gage, Booth, & Rowe, 2001). Thus, he argued, their use as a checklist for blame only served management at the expense of firefighters (Putnam, 2001a; see also Thackaberry, 2005). Putnam argued instead for investigations to focus on ‘‘human factors,’’ much like the aviation industry did in investigating accidents (Putnam, 1995; see also Thackaberry, 2004). ... Various other technical solutions emerged at the time, such as to replace the Fire Orders with a different set of 10 items (e.g., Withen, 2005); to reduce the number of items to four (e.g., Gleason, 1991), to clarify an essential subset that should never be broken (e.g., TriData Corporation [TriData], 1998); to remove redundancies among the Fire Orders and other lists (e.g., Goodell, 2002); or to revise the Fire Orders into a dynamic tool that takes sensemaking and updating into account (e.g., Putnam, 2001b; Weick, 1995). Although these proposals captured the attention of the safety community, they were largely ignored at the policy level. ... Multiple cultural functions. By 2001, the Fire Orders had also been called upon to serve various cultural functions well beyond their original purpose. In addition to serving the explicit functions of explanation and prevention (1957), the Fire Orders had served as a unifying symbol for the ‘‘confederation of cultures’’ (Tompkins, 2005) that made up the interagency network of wildland firefighters (after the creation of the NWCG in 1976). Later, when the Fire Orders were used as a checklist for blame, they served the functions of disciplining and dissociation (e.g., BLM & Forest Service, 1994; Forest Service, 2001; cf. Thackaberry, 2006). And, when the Secretaries’ zero tolerance memo clarified that the list was an absolute set of rules (Glickman & Babbitt, 1995), the Fire Orders were used to accomplish organizational purification (Thackaberry, 2005), while the list simultaneously stood as a threat of punishment. And, as ‘‘rules of engagement’’ (Williams, 2002), the Fire Orders became aligned with the recent military successes of the first Gulf War. ... Finally, the Fire Orders began to be invoked as a kind of memorial to the dead, particularly the Mann Gulch 13, a group of smokejumpers who had been killed in that Montana fire in 1949 (Alder, 1997; Maclean, 1993; Weick, 1993). The Mann Gulch [F]ire had been among the fires included in the 1957 trend analysis from which the original Fire Orders had been developed. In celebrating the successful survival of 73 firefighters who had become entrapped on the Butte Fire in 1985, for example, Rothermel and Brown (2000) argued that ‘‘in part they owe their lives to the lessons from the Mann Gulch [F]ire’’ (p. 9; see also Dombeck, 2000). ... Thus, even after the Fire Orders began to be discussed as potentially flawed for their intended purpose, and even after numerous alternatives surfaced, the multiple cultural functions now attached to the list made it difficult for the wildland fire community to modify or even get rid of the Fire Orders. For example, if this traditional list were to be suddenly scrapped in 2001, this might question the ‘‘private sacrifices of the dead’’ (Pyne, 1994, p. 19). ... The right story to change the list. Two fire veterans, working independently, stumbled upon the right narrative that would help the wildland fire community to move past this standstill. In a sense, they both argued to reclaim what they understood to be the spirit of the original 10 Standard Firefighting Orders, although they went about it in different ways. In 2001, Karl Brauneis, a veteran firefighter turned Fire Management Officer, circulated an open letter to firefighters that instructed them to ignore the 1987 revision and to return to the original ordering of the Fire Orders. His directive also emphasized moving up and down the list to ‘‘engage’’ and ‘‘disengage’’ from the fire as a way to capture the list’s ‘‘original intent’’ (Brauneis, 2002). ... John Krebs, a veteran firefighter turned instructor, promoted a similar perspective, but instead of appealing to firefighters, he attempted to influence policy at the top. He wrote a letter to Jerry Williams, then Director of Fire and Aviation for the Forest Service, arguing that the problem with the Fire Orders was simply that they had been reordered in 1987, and that the revision had diluted the ‘‘original intent’’ of the Orders. The solution, Krebs (1999) argued, was to change the list back to its original ordering (cf. Church, 2007). ... Krebs (1999) argued that the original list had been ‘‘deliberately arranged according to their importance’’ and ‘‘logically grouped to make them easy to remember’’ (p. 2). Aside from this appeal to reason, Krebs bolstered the credibility of the developers of the original list by pointing out that they had been ‘‘intimately acquainted with the dirt, grime, sweat, and tears of firefighting’’ and thus had been very well aware of how they had ordered the list. He also enhanced his own credibility by pointing out that he had been among the first group of firefighters to learn the original 10 Standard Firefighting Orders in guard school in 1958. Krebs’ letter also expressed pathos over the apparently unnecessary deaths of the South Canyon 14, and lamented, ‘‘Where have we failed to make fire behavior the most important thought in the minds of our firefighters?’’ (p. 1). ... Aside from the persuasiveness of the letter at a textual level, Krebs’ ‘‘back to basics’’ argument (1999) transcended the struggle that had been taking place over the authority of the Fire Orders. Specifically, it redefined the traditional meaning of the list in a way that was face-saving for both the agencies and for firefighters. Essentially, he argued, the community had had the right items all along; they had just had them in the wrong order. (Thus, by extension, firefighters could not really be blamed for their actions if they had been given the wrong list.) Neither was Krebs’ argument a threat to the various cultural functions that had become attached to the Fire Orders, such as their emergence as a memorial to the dead. After all, the Mann Gulch firefighters’ deaths had given rise to the original list of 10 Standard Firefighting Orders, and not the 1987 revision. ... A tool for ‘‘risk management.’’ Simultaneously, and perhaps unknowingly, Krebs also presented a view of the Fire Orders that aligned with a new managerial discourse that was emerging in fire management at the time: the insurance-industry-inspired discourse of ‘‘risk management.’’ which had been enabled by advances in probability theory (Bernstein, 1996). This also comports with Pyne’s (1997) observation that in the 1970s and 1980s the overarching approach to fire control was ‘‘risk management.’’; it was only a matter of time before managing ‘‘risk" would become a key part of doing so. ... Williams, the original recipient of the letter, had passed Krebs’ letter along to the NWCG Standards Working Team, whose members were persuaded by the argument to revise the list back to its original ordering (with the exception of Standard Firefighting Order number 10 which was changed to, ‘‘Fight fire aggressively having provided for [italics added] safety first’’). In their rationale, the NWCG explained that the Fire Orders were, and had always been, a tool for risk management because they had been ‘‘organized in a deliberate and sequential way to be implemented systematically and applied to all fire situations’’ (NWCG, 2003, p. 1). Furthermore, the team argued, the 1987 revision had changed the ‘‘organized in a deliberate and sequential way to be implemented systematically and applied to all fire situations’’ (p. 1). Thus, the revised list would ‘‘improve firefighters’ understanding and implementation’’ of the Fire Orders (p. 2). In other words, the NWCG accepted Krebs’ argument, but simultaneously translated it into the new discourse of risk management in passing it along to others. ... Although the primary Fire Order was now back at the bottom of the list, not only its wording but also its meaning had changed: By going through each step in sequence, firefighters were presumably mitigating key risks one by one. Thus, once they reached the bottom of the list (i.e., ‘‘having provided for safety’’) they had earned a kind of organizational permission to ‘‘fight fire aggressively.’’ This stands in sharp contrast to the original 1957 meaning for the 10th Fire Order as a highly personal process of individual judgment formation, where the firefighter could work through the list over a series of fires to become the‘‘coolhead’’ who could simultaneously keep fires small and people safe, and therefore be regarded as a hero. Now, in this revisionist history, the Fire Orders were being described as a kind of ‘‘recipe’’ for safe organizing. ... The 1957 list could not really have been a ‘‘risk management program’’ because that discourse did not exist in 1957. Furthermore, the subscript to the original 1957 list had clearly suggested that not all items were meant to apply to all fire situations. Nevertheless, the ‘‘back to basics’’ rhetoric reclaimed, but also redefined, the traditional meaning of the Fire Orders, while its alignment with the emerging risk management discourse helped the wildland fire community to revise the list and to move forward. ... A permission slip for aggression. Now that the context for the 2003 revision has been explained, this third iteration of the Fire Orders can be analyzed. As evident in Table 4, the items have been rearranged back to the original order, but they have also been categorized into ‘‘Fire Behavior,’’ ‘‘Fireline Safety,’’ and ‘‘Organizational Control.’’ In this way, the list of Fire Orders now resembles a PowerPoint slide. As described above, the items are presented as a recipe for organizing that applies to all fire situations, such that after each successive risk is mitigated, firefighters will have earned the right to fight fire aggressively. According to the qualification at the bottom, the Fire Orders are still considered to be ‘‘firm’’; however, they are no longer called ‘‘rules of engagement.’’ And, the admonition that ‘‘We Don’t Break Them, We Don’t Bend Them’’ is now presented in all capital letters, as if it had been trademarked. ... Additionally, a new sentence was added that states that ‘‘All Firefighters have a Right to a Safe Assignment.’’ This statement reflects the influence of the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), who has been investigating wildland fire fatalities since 1994, and who has issued ‘‘serious’’ and ‘‘willful’’ citations to the Forest Service and to the BLM for failing to provide a safe working environment for firefighters.5 As it applies to the Fire Orders, this statement means that employees can now question assignments that seem to violate the Fire Orders or otherwise seem too dangerous. ... The revised list was first brought to bear on the 2003 Cramer Fire that killed two helitacks in Idaho. In that investigation report the Fire Orders were described as a checklist for supervisors to organize a crew safely, but also as a checklist for firefighters to pose questions ‘‘whenever they have concerns about their personal safety’’ (Forest Service, 2003, p. 68). More recently, there has been a trend away from invoking the Fire Orders in accident investigations, such as in the joint CalFire/Forest Service investigation into the Esperanza Fire that claimed the lives of five firefighters in October 2006, which never mentions them at all. ... Additionally, the Forest Service in particular is now starting to qualify the list of Fire Orders as ‘‘foundational firefighting principles’’ instead of hard and fast rules, as part of a move toward specifying fire suppression ‘‘doctrine’’ (Hollenshead, Smith, Carroll, & Keller, 2005). In fact, in 2006, Forest Service attorneys used the argument that the Fire Orders were not rules of engagement to successfully defend the agency in a civilian lawsuit brought by Montana homeowners whose houses had been destroyed by an escaped prescribed fire (Backfire v. US, 2006). The homeowners had sued the Forest Service on the basis that actions taken by its employees had not adhered to the Fire Orders. However, the Forest Service successfully argued that the Fire Orders were not rules of engagement for firefighters and thus the agency was not held liable for the losses. ... Despite these recent qualifications to the authority of the Fire Orders, at the time of this writing, the list remains ‘‘on the books’’ in the Forest Service Manual, and remains an NWCG standard for all wildland firefighters.

Standard Firefighting Orders (1957- 1986)

Keep informed on FIRE WEATHER conditions and forecasts.

Know what your FIRE is DOING at all times* observe personally, use scouts.

Base all actions on current and expected BEHAVIOR of FIRE.

Have ESCAPE ROUTES for everyone and make them known.

Post a LOOKOUT when there is possible danger.

Be ALERT, keep CALM, THINK clearly, ACT decisively.

Maintain prompt COMMUNICATION with your men, your boss, and adjoining forces.

Give clear INSTRUCTIONS and be sure they are understood.

Maintain CONTROL of your men at all times.

Fight fire aggressively but provide for SAFETY first.

Every Forest Service employee who will have firefighting duties will learn these orders and follow each order when it applies to his assignment.

Source. McArdle (1957, p. 151).

10 Standard Fire Orders (1987-2002)

Fight fire aggressively but provide for safety first.

Initiate all action based on current and expected fire behavior.

Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

Ensure instructions are given and understood.

Obtain current information on fire status.